Unless you’re living under a rock, you probably have heard about ChatGPT by now. The Internet has been buzzing with new technologies for the past few months. Tools that would have taken months, possibly years, to build are being developed just over a weekend of hacking. I truly believe that we’re living in one of the most exciting times in history.

Naturally, researchers are exploring the applications of large language models (LLMs) in various domains. In this blog, we’ll explore some of the ways in which LLMs can be used in chemistry. For each task, we’ll do a literature survey to check existing work and progress. Let’s dive in.

1. Molecule editing using natural language

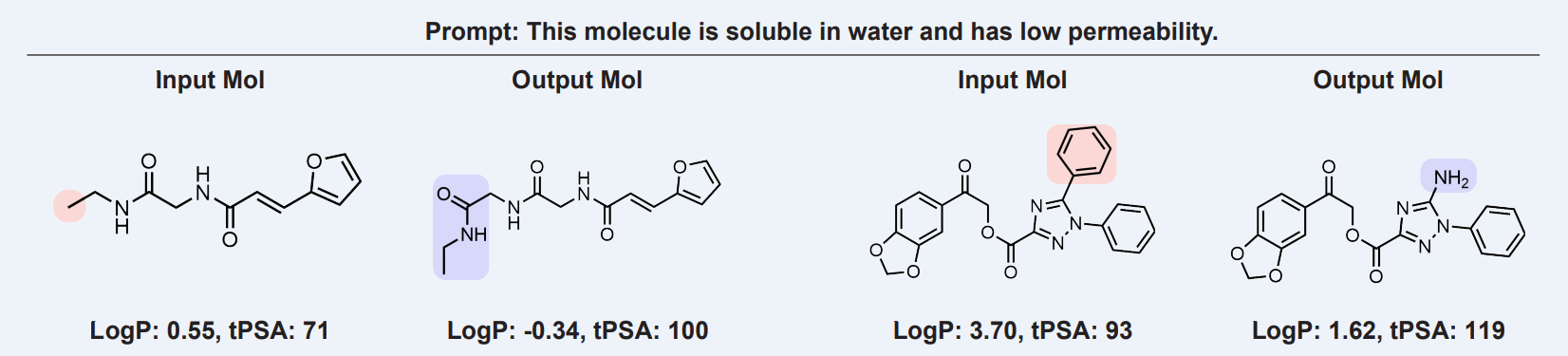

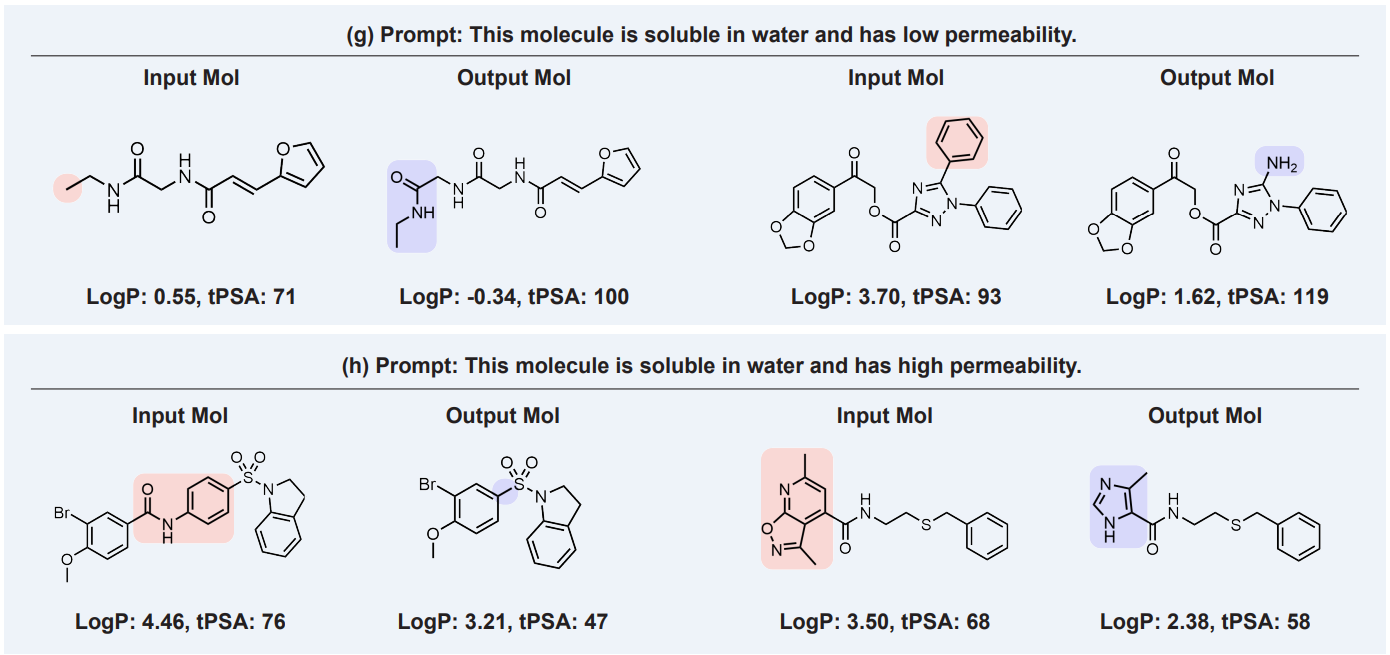

Finding molecules with a desirable balance of multiple properties such as solubility, permeability, and the absorption coefficient is a major challenge in drug discovery[1]. Sometimes, a molecule has the right amount of one property but is missing another. In such cases, modifying a part of the molecule such that desired second property is met while making sure the first property is also kept similar is a challenging task. Scientists generally try to use their domain expertise to tackle this problem but it’s inefficient. Large Language Models can help with this by modifying an input molecule based on a text prompt. See the below image as an example. Given the prompt “This molecule is soluble in water and has low permeability”, the model modified the input molecules to desirable properties.

Literature Review

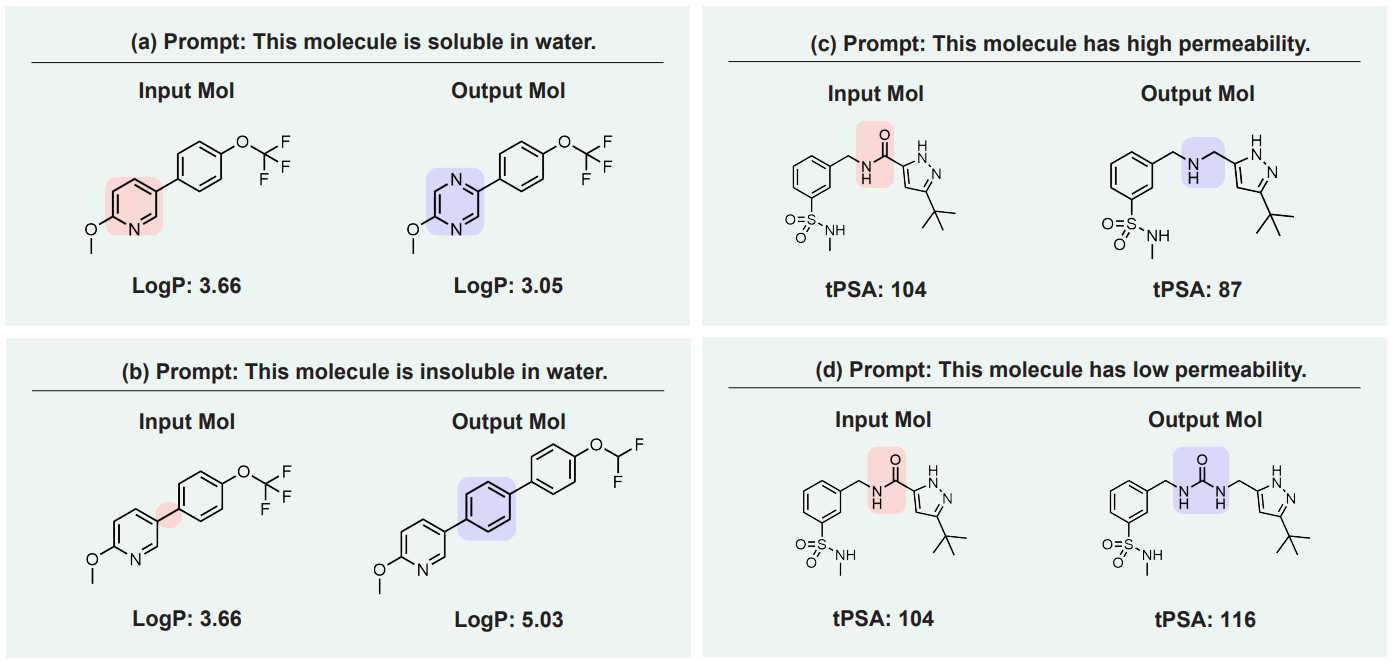

Liu et al[2] used a multi-modal approach to develop a model called MoleculeSTM by jointly learning molecule’s chemical structures and textual descriptions. Most ML and DL models only use chemical structural information to make predictions while ignoring the vast textual information available about the molecule from the books and literature. The authors used a contrastive learning strategy to combine both kinds of data. They cover two categories of text prompts (they actually cover four categories but we’re limiting the scope to just chemistry):

-

Single-objective editing is the text prompt using a single drug-related property for editing, such as “molecule with high solubility” and “molecule more like a drug”. For example:

Source: arXiv:2212.10789 -

Multi-objective (compositionality) editing is the text prompt applying multiple properties simultaneously, such as “molecule with high solubility and high permeability”. For example:

Source: arXiv:2212.10789

2. Molecular property prediction

Let’s take a step back from molecule editing. We talked about knowing the various properties of the molecules. But how are these properties calculated? The traditional way is to conduct experiments in the lab and observe the values. As you might have guessed, this is again resource-consuming. Sometimes, scientists manufacture only minuscule amounts of candidate molecules which might be enough to compute a few properties but not all. Once again LLMs can help here.

You might wonder why not use traditional Machine Learning or Deep Learning models like Graph Convolutional Networks for this task. And the answer is that yes we can. In fact, Wieder et al[3] in their review paper, discuss 80 different variations of Graph Neural Networks across 63 publications used for this task and shows a total of 16570 papers published for molecular property prediction! This was over 2 years ago (Dec 2020), you can only imagine the situation now.

So what’s the issue here? Majorly two:

- These models don’t often leverage the vast amount of information available about chemistry in the form of a text. When scientists make decisions, their intuition is driven by years of study and experience and not just the molecular structure alone.

- Lack of data availability. Acquiring a high-quality dataset is one of the biggest challenges in drug discovery. The reasons could vary from the monetary cost to proprietary data. Training on a smaller dataset can not only limit the model complexity but also the chemical space a model can be applied to.

By training on hundreds of thousands of Chemistry books and relevant literature papers, LLMs can “learn” Chemistry. When applying them to make a property prediction, this knowledge can be equivalent to a Chemist’s intuition. Since the model inherently “understands” chemistry”, this can solve the issue of limited data availability.

Literature Review

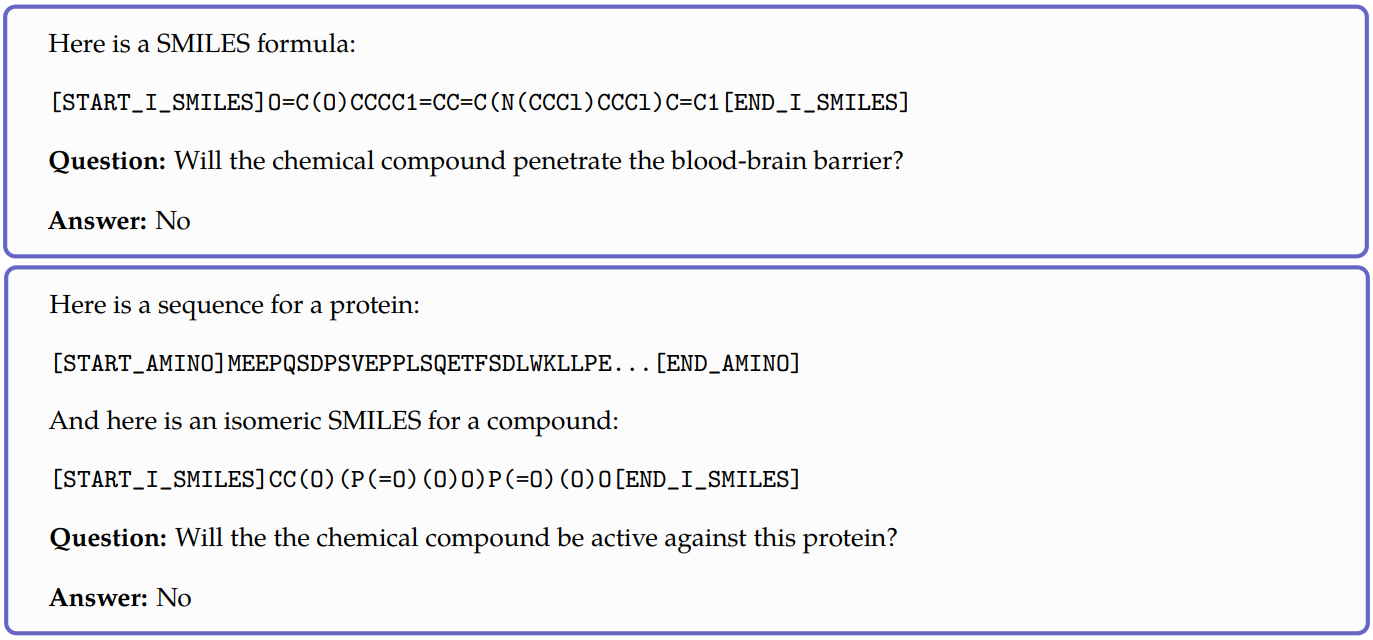

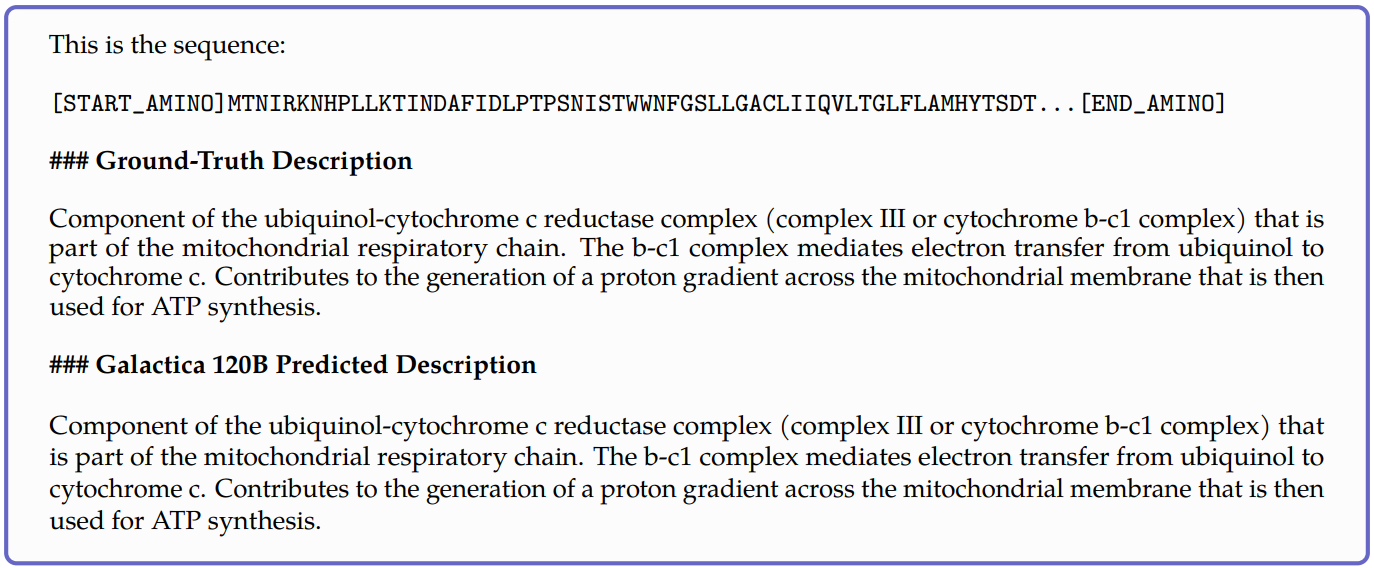

Meta’s Galactica model[4] is one of the few papers to attempt this. It is a large language model that can store, combine, and reason about scientific knowledge. The model is trained on a large scientific corpus of papers, reference material, knowledge bases, and many other sources. Although their work wasn’t exclusively focused on molecular property prediction, they showed that the model showed potential to have a chemical and biological understanding for various prediction tasks. To evaluate the model performance, they pose the input as text. Here are two examples:

As you might have noticed, this model is only limited to classification tasks. In my research, I couldn’t find any other work done on this so there’s lot of scope. Naturally, this task can be expanded to other similar problem statements like reaction product prediction, reaction yield prediction, etc.

3. Interactive retrosynthesis planning

New drug development is a complex process with high costs and risks. It usually takes billions of dollars and ten or more years for an innovative drug to be developed and finally put on the market[5]. Therefore, it’s essential to find an optimal path to synthesize a molecule.

In simplest terms, retrosynthesis planning is the process of converting a target molecule into individual reactant molecules. But why would we want to do this? Well, once a target molecule is identified and it’s optimized for desired properties, we also need to figure out how to synthesize it. We need to figure out what combination of reactants and synthesis path can lead to this particular target molecule optimally.

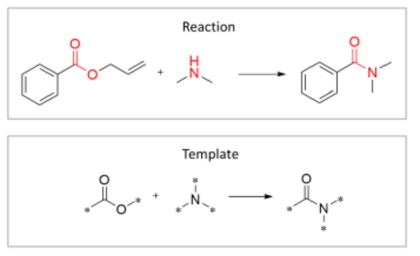

Retrosynthesis is a particularly challenging task due to the sheer number of possible transformations at every step. Szymkuć et al[6] estimate that there can be as many as 10000 transformations at every step. Further, multi-step retrosynthesis (when identified reactants can’t be purchased themselves and need to be further synthesized retrosynthetically) makes the process even more complicated. A template-based approach has been a widely used method for retrosynthesis planning where predefined rules are created to guide a reaction. The below example illustrates this approach. The red highlighted parts represent the reaction centers of the chemical reaction.

A major criticism of this approach is its inability to provide accurate predictions for novel target molecules or reaction types out of their knowledge base[7]. In recent years, there has been tremendous progress in using AI methods for predicting the synthesis routes. Zhong et al[5] compares and summarizes various ML and DL-based methods across 40+ research papers. However, similar to molecular property prediction, these models don’t leverage textual information. Additionally, LLMs can also offer live interaction with the model where users can continuously modify the requirements to reach an optimal synthesis path. Lastly, the LLM model can also explain why it chose a specific synthesis route over another making them more interpretable than usual deep learning models.

Literature Review

In my research, I could not find any work that’s been done already on this but that was expected since LLMs are a relatively new discovery. However, I did come across a tweet from Prof. Andrew White from the University of Rochester where he talked about a potential paper. Wang et al[8] proposed an interactive planning approach based on Large Language Models to train multi-task agents for the Minecraft game. In this game, to perform a specific task (say building a sleeping bed), multiple sub-tasks have to be completed (say acquiring wool for bedding, getting wood, getting screws, etc). Some of these sub-tasks themselves may require additional tasks to do (say mining ground for iron to build screws which in turn might require finding a shovel to dig). Retrosynthesis have something of a similar process. There’s a goal of identifying an optimal synthesis path (like building a bed) and to achieve it, multiple sub-goals have to be completed (like mining for wood). Sometimes, a path might not be feasible (goal failed) so we can ask the LLM (explainer) to come up with a new plan. If you want to learn more about it, I wrote a summary of this paper here.

4. De Novo Molecule Generation

So far we discussed molecule editing, molecular property prediction, and retrosynthesis planning. In all three cases, we already discovered a target molecule. But what if we don’t know what molecule will bind to a particular protein or will cure a disease? LLMs can help here by taking a text prompt as input and generating a suggested molecular structure as output. This prompt can, for example, contain information about the molecule, its structure, and its target proteins.

Literature Review

Generative deep learning has been somewhat successful in de novo drug design and is getting lots of attention from the research community. Grisoni[12] in his review paper discusses various state-of-the-art models for de novo drug design. Generative models are trained on SMILES strings and generate new molecules in the form of a string. However, once again, these models don’t use the textual information available out there in the literature.

Meta’s Galactica model[4] attempted a somewhat opposite task where given a protein sequence, the model tried to predict its function as shown in the below example.

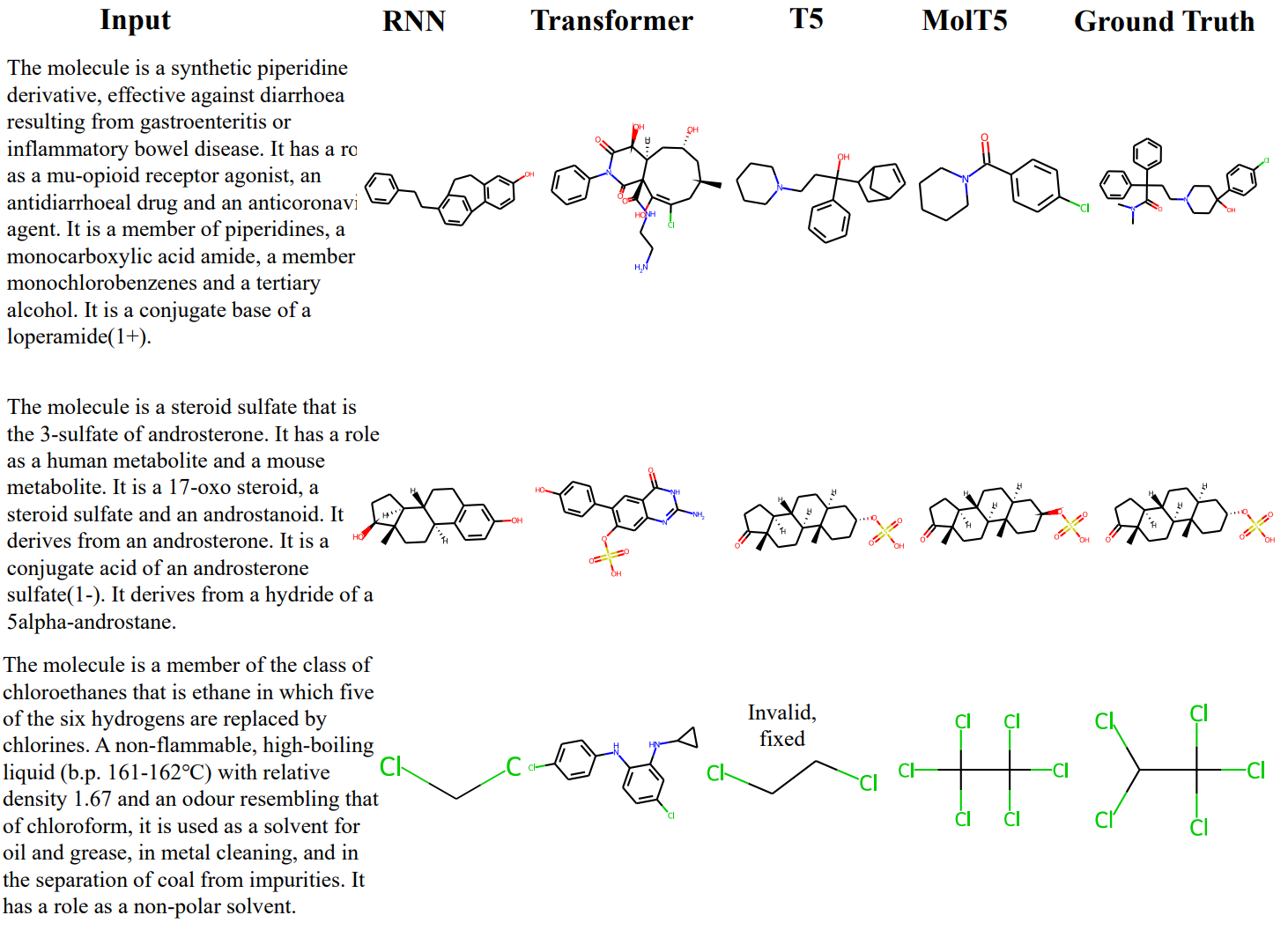

One of the most notable works has been done by Edwards et al[14]. The authors propose a model called MolT5 that was trained for two tasks:

- Molecule captioning, where a description is generated for a given molecule

- Text-based de novo molecule generation, where a molecule is generated to match a given text description

It was jointly trained on both molecule string representations and natural language text. Here are a few relevant examples:

5. Knowledge retrieval

We just discussed about generating de novo drugs from textual knowledge. But where does this knowledge come from? You could say that a scientist might use their experience but that’s not always helpful. There’s so much knowledge out there, it’s incomprehensible for a human mind to read or learn everything. Traditionally, scientists have to manually search through databases and literature to find relevant information on chemical reactions, properties, and other topics. However, LLMs, once trained on chemical literature, can find relevant information in real time.

There are two kinds of information a user might need:

- Static knowledge: Information that doesn’t change over time. For example, the properties of a Carbon atom won’t change over time and is static knowledge. Experiments with ChatGPT have proved that LLMs can handle this kind of information fairly well.

- Dynamic knowledge: When a new research paper is published, an LLM model might not necessarily produce accurate results since it hasn’t seen the new information. In such cases, relevant documents or research papers can be passed as a context and then ask a question. This ensures that the model is extracting the latest information and answering the question. Proprietary clinical or lab experimental documents have a special use case here. Such documents contain a vast amount of information that can’t be made public for proprietary reasons and may be difficult to summarize or read through for humans. These documents can be passed as context and ask the model to either summarize or extract important insights.

Literature Review

Dan Shipper in his article shows how providing the right context can help get accurate information out of LLMs.

With libraries like LangChain, it’s become extremely easy to build a QA-chatbot over specific documents using LLMs. Paper-QA is one such chatbot for doing the question and answering from PDFs or text files using GPT-4 model. A demo for this package can be found here. In this demo, you can upload your own documents and then ask relevant questions and the model will try to answer by grounding responses with in-text citations.

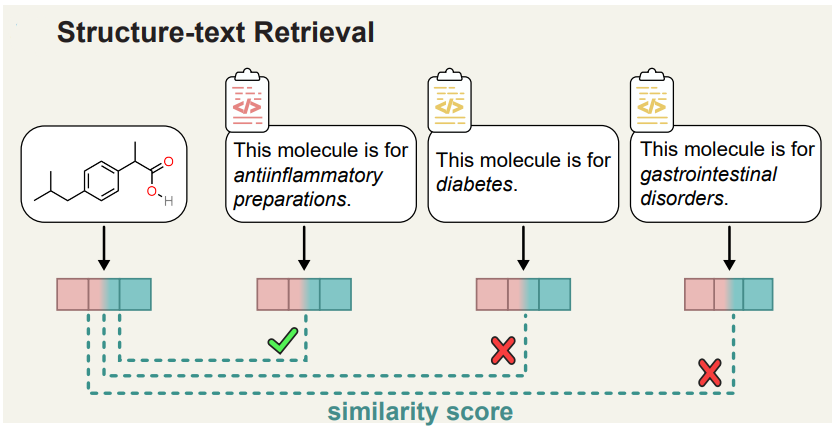

Liu et al[2] attempts a slightly different task where given a chemical structure and T textual descriptions, the retrieval task is to select the textual description with the highest similarity to the chemical structure (or vice versa). This is appealing for specific drug discovery tasks, such as drug re-purposing or indication expansion[15, 16]. The below figure illustrates the entire process.

There are many tools on the internet that claims to be great research paper summarizer and insights extractor. Some examples being Paper Digest, Content Mine, Elicit, SciSpace Copilot, and Scholarcy. I’ll let you be the judge of how good they are.

6. Input file generation

Have you ever tried using software like NWChem or Gaussian? These tools are designed for optimized quantum computations on supercomputer clusters and require specialized input file formats unique to each software. These files can be very tedious often requiring knowledge of computer hardware and system architecture. These kinds of roadblocks shouldn’t hinder a scientist’s progress. LLMs can help here by generating these files using natural language prompts. For example, you can prompt it to generate an input file for NWChem by providing the molecule name, basis sets, and a list of desirable properties to be computed.

Literature Review

In literature, this has been a largely unexplored problem from the perspective of Machine Learning. There are some rule-based tools like OpenBabel[13] that can generate such files in various formats but these tools are limited in their scope. For example, if you want to use a specific basis set, say CCSD, in NWChem computations, you’d need to know the exact name of the property and the format of the file. Hocky et al[9] and White et al[11] experimented with Codex[10] to generate code for Chemistry tasks. They also showed that GPT-3 based Codex was able to generate input files for Gaussian software successfully. Here’s an example:

Final thoughts

As we saw in this article, LLMs have the potential to revolutionize the way we approach chemistry problems. From molecule editing to retrosynthesis planning, and knowledge retrieval to prediction tasks, LLMs can help researchers to be more productive. While the researchers are making impressive progress in developing new techniques and models that leverage the power of LLMs, a lot more work is yet to be done. With more research and development, we can expect to see even more exciting applications of LLMs in chemistry in the coming years.

References

- He, J., You, H., Sandström, E. et al. Molecular optimization by capturing chemist’s intuition using deep neural networks. J Cheminform 13, 26 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13321-021-00497-0.

- Shengchao Liu, Weili Nie, et al. Multi-modal Molecule Structure-text Model for Text-based Retrieval and Editing. arXiv:2212.10789, Dec 2022. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2212.10789.

- Oliver Wieder, Stefan Kohlbacher, et al. A compact review of molecular property prediction with graph neural networks. Drug Discovery Today: Technologies, Volume 37, 2020, Pages 1-12, ISSN 1740-6749, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ddtec.2020.11.009.

- Ross Taylor, Marcin Kardas, et al. Galactica: A Large Language Model for Science. arXiv:2211.09085, Nov 2022. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2211.09085.

- Zipeng Zhong, Jie Song, et al. Recent advances in artificial intelligence for retrosynthesis. arXiv:2301.05864, Jan 2023. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2301.05864.

- Szymkuć S, et al. Computer-Assisted Synthetic Planning: The End of the Beginning. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2016 May 10; 55(20):5904-37. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201506101.

- Yinjie Jiang, Yemin Yu, et al. Artificial Intelligence for Retrosynthesis Prediction. Engineering, 2022, ISSN 2095-8099. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eng.2022.04.021.

- Zihao Wang, et al. Describe, Explain, Plan and Select: Interactive Planning with LLMs Enables Open-World Multi-Task Agents. arXiv:2302.01560, Feb 2023. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2302.01560.

- Glen M. Hocky, Andrew D. White. Natural language processing models that automate programming will transform chemistry research and teaching. Digital Discovery, 2022, 1, 79-83. https://doi.org/10.1039/D1DD00009H.

- M. Chen, J. Tworek, et al. Evaluating large language models trained on code. arXiv:2107.03374, Jul 2021. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2107.03374.

- Andrew D. White, Glen M. Hocky, et al. Assessment of chemistry knowledge in large language models that generate code. Digital Discovery, 2023, 2, 368-376. https://doi.org/10.1039/D2DD00087C.

- Francesca Grisoni. Chemical language models for de novo drug design: Challenges and opportunities. Current Opinion in Structural Biology, Volume 79, 2023, 102527, ISSN 0959-440X. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbi.2023.102527.

- Noel M O'Boyle, Michael Banck, et al. Open Babel: An open chemical toolbox. Journal of Cheminformatics 2011, 3 (1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1758-2946-3-33.

- Carl Edwards, Tuan Lai, et al. Translation between Molecules and Natural Language. arXiv:2204.11817, Nov 2022. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2204.11817.

- Zeng Z, Yao Y, et al. A deep-learning system bridging molecule structure and biomedical text with comprehension comparable to human professionals. Nat Commun. 2022 Feb 14; 13(1):862. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-28494-3.

- Aggarwal, S. Targeted cancer therapies. Nat Rev Drug Discov 9, 427–428 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd3186.

ChemicBook

ChemicBook

Share it on Twitter Facebook LinkedIn